By Josh Hellstrom

I Thru-Hiked the Colorado Trail in 2015 and came into it with no real distance-hiking experience. This summer I hope to hike the 80-mile Collegiate West portion, but like everyone else, I have to make plans with the COVID-19 virus restrictions. My feeling is, what better way to achieve “social-distancing” than on a mountain trail? Of course, we will have to wait this out and see, but I am still making plans. I know the Segment 1 section through Waterton Canyon is presently closed, but that could change at any time. In 2015, Segments 1 and 2 were closed due to a bridge washout, so I started at Segment 3 (Little Scraggy Trailhead) and came back at the end of my Thru-Hike to finish Segments 1 and 2 (28.3 miles that I did in one day with a light pack).

If you plan to hike the CT this summer, or anytime in the future, I hope that sharing some of my Thru-Hike experience might help you with your planning and expectations.

I am a Florida guy but have spent lots of summers hiking in Colorado, summiting 14ers had two daughters living in Colorado, but my experiences were all-day hikes with light packs. Thru-hiking is a whole different animal. My daughter Mackenzie hiked the first 50 miles of the CT with me and on Day 2 said, “These packs are a real difference-maker.” It was the understatement of our first week.

I did my research on the CT, as you are probably doing now, and talked to anyone that had knowledge of the Trail. I knew it was 486-miles long. The average elevation was going to be over 10,000 feet, and the up/down would be about 90,000 ft. 90,000 feet is more than three Mount Everests…from sea level, not base camp. I reckoned the distance to be about the same as crossing the state of Florida east/west three times up in the north-central area where I live and having Mount Everest in the center of the state. Up and down. My math didn’t make the task seem any easier, but did not intimidate me either, as it should not intimidate you.

I was 56 when I started the CT. I was recovering from Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma and still on a residual chemotherapy routine where I would do my chemo treatments only every 28 days and the drugs had little effect on my training. Cancer, on the other hand, had a great deal to do with my drive. I think a good question for you is…what is your drive?? If you are able to define your “drive” before you set out, I believe your odds of completing the Trail will be significantly greater.

I bought a good pair of Soloman low-cut hiking shoes to carry me on the Trail and broke them in for about two months at 67’ above sea level training in Gainesville, Florida. Some days I just hiked without my pack or ran stadiums steps at the UF, but as time drew closer I loaded my pack with 35 pounds of dead weight (usually just blankets and barbells) to get used to my pack, the weight, and the strain on my shoulders. I do not regret a single day of training.

Because of my age, I was much more cautious about my health than I would have been as a younger man, and early on I decided to take an 8-Day Wilderness First Responder (WFR or Woofer) class in Colorado, outside of Vail, where my daughter Alexa was living. I would highly recommend the class to anyone hiking the CT, and anyone who spends time in the backwoods. There are WFR class options all over the country. Check online. The class cost about $800 (at least in 2015) and I felt like it was one of the best, most practical, educational experiences of my life. Our instructor, Sarah, taught classes like this part-time, worked as a paramedic, and drove an ambulance in central Colorado. She is also a rock and ice-climbing guide on the side. Pure badass, but kind and generous about sharing her experiences and knowledge. She is also a Type II diabetic and managed her insulin and sugar levels wearing a monitor. Her drive and knowledge were incredibly inspirational.

As much as I loved the class and took everything seriously, the class was very hard for me. I had not been a student in a classroom in more than 30 years. I have no special medical training and couldn’t remember much of anything about anatomy or biology classes from high school or college. There were 10 other guys and one other woman in the class, all younger than me, and most, smarter than me. As Sarah cruised through the wilderness medical textbook, I thought my mind might actually explode. Each day got better and Sarah was patient with me. So were the other students. They were a mix of ski guides, travelers, and adventurers who all had their reasons for taking the class. I just wanted to feel like if I got in a jam on the Trail, or ran across someone who was hurt, that I might actually know what to do. There are long stretches of the Colorado Trail that are a long way from anywhere, and a long way from help.

I learned a ton of helpful techniques. I learned the difference between HAPE (High Altitude Pulmonary Edema) and MI (Myocardial Infraction), how to treat a broken arm, how to make a litter (backwoods stretcher), and tons of other stuff that can happen to the human body in the wild, where cold, heat, accidents, and wild animals can turn a lovely day hiking into a life-or-death experience.

I hope I never have to use the techniques we learned in the WFR class, but I feel much more prepared to help myself my family members, and maybe a total stranger I could meet in the wilderness who had some kind of health misfortune. One of the main things we learned in the class was to offer a solid assessment of a bad situation and to go through a list of questions to determine the extent of the injury. What happened? How serious is the injury? Should they be moved at all? Does the victim need an airlift? Could they walk out on their own? Are there additional injuries that are less apparent?

We weren’t trained to treat all injuries, just mostly assess and apply temporary treatment until the real pros got there. Having the confidence to step in to help when other people might step back is also vital, perhaps lifesaving. Our teacher, Sarah, did it all the time. She had countless stories, often about well-intended adventure-seekers, who mix planned, misjudged, or were just plain unlucky. Watch the TV show, “I Shouldn’t Be Alive” and you will see that most well-intended outdoors adventures that go wrong are usually a simple matter of three things going astray: improper prep (maybe not enough food, water, or weather gear), a small mistake (a simple wrong turn), and then a little bad luck (often weather, but could be a misstep or a broken ankle). Those things together can lead to disaster.

In August 2018, I was enjoying a vacation with family in Breckenridge and took my group up to about 12,500’ elevation on a hike to see if there was anyone in our group that might have trouble if we tried the pretty simple Quandary Mountain 14er the next day. We hiked across the valley from Quandary and watched the peak get clouded in during the afternoon. It was cold and damp, but no really bad weather and no lightning, at least where we were. But on Quandary, a young couple in their 20’s had summited in the early afternoon (later than they should have) and got disoriented during the cloud cover, and then light snow covered the trail down. They hiked off the wrong side of the mountain and called for rescue sometime before dark. It took 13 responders eleven hours to haul the two hikers off the mountain, and they almost certainly would have died of hypothermia without rescue. And that was August. Just a lesson.

During our class, Sarah got a text that one of her rock climbing friends had fallen 40’ and landed on a rock and snapped his spine. His girlfriend was with him and even though Sarah said he was a knowledgeable climber, something went terribly wrong. He may not have made any of the three mistakes, but something went horribly wrong. His girlfriend called 911 and administered CPR for 45 minutes waiting for help, but he never revived and died on the scene.

I asked Sarah at the end of the week why she did the adventure guiding, rock-climbing, and ice-climbing. Why put yourself at such risk?? She told me in no uncertain terms that she was always prepared. Always. That she never wanted to be one of those, “Well, at least she died doing what she loved” stories. She prepared for everything within her power because she was responsible not only for her own health, but the health and well-being of clients who wanted to learn rock or ice climbing. She studied the weather, pre-planned specific routes, immaculately maintained her equipment, and tried to consider anything and everything that could go wrong. And even losing a climbing friend that week did not deter her from doing what she loved. But it was easy to see how hurt she was at the loss of her friend.

I hope you will realize the point of me going into some detail about that class was that unexpected shit happens. If you are going to spend 30-40 days hiking the Colorado Trail, some shit is going to happen to you along the way. Count on it. Hopefully nothing serious, but the more prepared you are, the better off you will be. And there is a very good chance you will meet someone who had not prepared well and may need your help.

On the last day of the WFR class I was driving on Highway 24, south of Minturn, Colorado, at about 6:30 in the morning. The highway parallels a section of the CT. There were no other cars and I saw a magnificent mountain lion cross the highway in front of me. The big cat dashed into the bushes and I pulled over and rolled down the passenger window. Then he popped his head up and stared at me. We had our moment, which I will remember forever, and then without even causing the bushes to move, he was gone. I waited to see where he would emerge, but he had vanished. I was amazed at his size, the thickness of his tail, his grace, and his stealth. I knew we would be sharing that section of forest in a few weeks when my hike would begin.

So prepare for the worst and expect the best. This hike is going to change the way you see the world. At least it did for me. All of us have our reasons for doing the things we do. If you are considering Thru-Hiking the CT, you probably have a good reason. But a lot of people don’t finish. I think the statistics are about 50% don’t finish for any number of reasons; injury or illness, loneliness for a loved one, even a pet, financial hardship, or just because it was harder than they expected. For me, once I got the go-ahead from my wife and another go-ahead from my cancer doctor, I was on a high that I would maintain for months leading up to the summer. The unknown parts were intriguing to me, shopping for lightweight gear was fun, putting together my plan, and watching it unfold was on my mind all the time. I was all-in and super-stoked.

I also watched lots of videos of other people doing the CT Thru-Hike. The problem with those videos, like those remodel HGTV shows that totally rehab a piece of crap house to utter glory in 23 minutes of TV time, is there is just no way to explain time on the Trail. Time slows down. It elongates. It does not condense. That is one of the beautiful things about it. You will see it. 3-4 days can feel like two weeks because every day is new. Every challenge is in front of you. You will look out across expanses that don’t really seem doable, light gray mountain images so far ahead that they don’t seem real, and yet that is exactly where you will be in a few days, as far as you can see. And you will look back across that same expanse that you thought was impossibly far in front of you and realize, if I could do that, maybe it is possible…. A YouTube highlight reel of the Thru-Hike may give you some good ideas of what to do and maybe what not to do, but it will not prepare you for the grind.

Day One, not two hours into the CT hike, my daughter Mackenzie and I met a guy whose hiking partner had just bailed on him. His buddy hiked no more than 2 miles and made an abrupt turnaround. “This is not gonna work for me,” he said and he made his friend turn around and drive him back to Denver to fly home. I was flabbergasted. “No shit,” I said. “No fucking shit” was his reply.

An hour later we hiked past a woman who looked about half my size and was carrying more weight than me. She was with her boyfriend/husband and they both looked uncomfortable. She even dangled a heavy pair of “spare boots” off the back of her pack. She was covered with sweat and complained that her feet were already blistering. She looked like Reese Witherspoon in the movie, “Wild”, at the beginning when she had so much weight in her pack that she couldn’t stand up. I didn’t see how she could possibly finish when she looked defeated not three hours in. But you know what, against all odds, I saw her on Day 38, not 5 miles from the Durango terminus point, a huge smile on her face ready to complete the Thru-Hike.

“I know you!” We both said on Day 38 and was genuinely surprised and so proud of her and her boyfriend. She wasn’t dangling any spare boots, was clearly thinner than when I first saw her (so was I, by nearly 30 pounds), and she said, “I wanted to do something big, and I am almost there!” I gave her a hug and a high-five and cruised toward the end. The brotherhood/sisterhood toward other Thru-hikers and hikers, in general, is one of the most beautiful things about the Trail. As much as I love John Muir and his love of all things mountain, it is often the people you meet on the Trail, those who share the “grind’ with you that will stick in your memory. Not just those who share the grind, but people with energy helping you make your way. You will see. I truly believe if you recognize that energy from others, and draw upon it, it will help you crush any doubts, and build you into a stronger human being. It is what we can do for each other.

So when you plan for this adventure, plan wisely, and open yourself up to the positive energy that is out there.

“This is your day.

The mountains are calling

So get on your way!”

Dr. Seuss

And break in your hiking boots. I chose low-cut, trail runner shoes at the advice from a book called, “Ultralight Backpackin’ Tips” by Mike Clelland. He has excellent tips to cut weight, to convince you of gear that is essential and what is non-essential, and his advice was to go light with the shoes because you are literally going to take a million steps and if your shoes are a one-half pound lighter than the next guy, that is half a million fewer pounds you are going to lift with your legs over the course of the CT. It made sense to me. Clelland also writes about not stopping your hike just because it is raining, offers clever ways to clean your butt after a poo, and how, and you will see, that you will stink while sweating and hiking without being able to regularly bathe. So get over it. You are gonna stink.

I didn’t really notice how stinky I was (a strong combo of body odor and campfire smoke) until I crossed Highway 9 between Frisco and Breckenridge and took the free trolley bus into Breckenridge for a huge burger, three giant glasses of fresh clean water with ice, and two craft beers. A very kind waitress actually sat near me (she was brave or her olfactory senses were pretty dull) as I isolated myself from most other tables and we talked about the Colorado Trail. She was a hiker and intrigued enough with the conversation to put up with my stinkiness. I ravaged the food and drink, and actually was anxious to get the hell out of town and back on the Trail, back to camping in the woods. Civilization feels very different even after a mere week. You will see. I hiked 4 miles up toward the Breckenridge ski range and felt like I was 100 miles from anywhere, and exactly where I wanted to be.

Further motivation for me to complete the Thru-Hike was a fund-raising effort that my daughter, Mackenzie, organized through GoFundMe. I wrote about my intentions and social media did what it does and in what seemed like no time we had raised over $10,000 for the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS). It was humbling. A little more than $20 for charity for every mile I covered. You do not have to be a cancer patient to raise money. If you have a favorite charity, think of doing something like that. You are going to do the work anyway, so you might as well raise some money for a good cause while doing it. Countless times, when I was exhausted, or getting chomped on by a mosquito hoard while trying to filter water, I would think of the fundraiser, of all those friends and family that had faith in me to finish, and of those who might not ever be able to do something like I was doing because of a disease or some other problem and it just kept me going. It kept me going for them. There are a lot of good causes out there. Pick one. If you stink at organizing a fundraiser, find help. You’ll be glad you did.

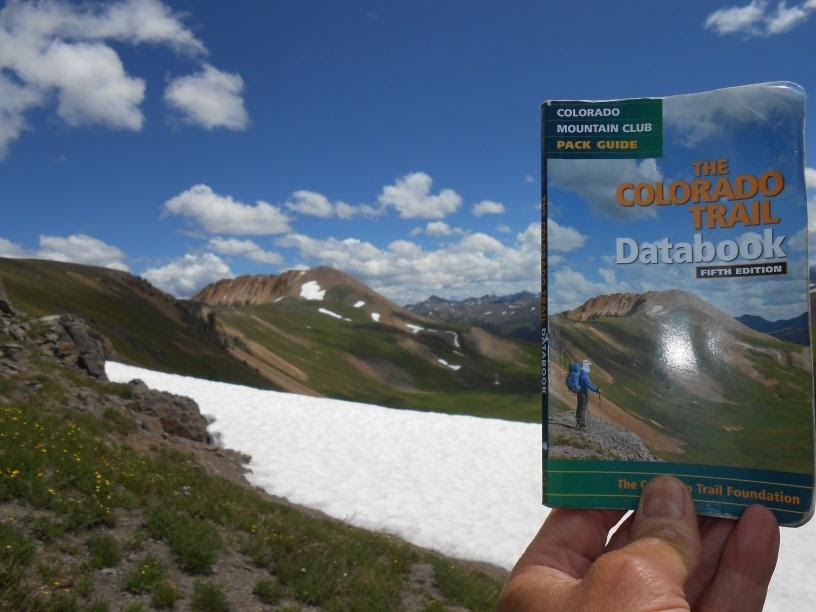

I ordered the Colorado Trail Databook and referred to the book daily on the Trail. If you don’t get anything else, get the Databook. You can order one online from The Colorado Trail Foundation. It is not perfect, but it details mileage, altitude gain/loss, checkpoints, camp spots, and water. It shows highway crossings and distances to close towns to resupply. It is an absolutely vital information book. The details about water are the most important. You want to be near water when you camp, for evening and morning meals, to hydrate at the end of the day, and to fill up to start the new day. You also want to know where the next water source is when you are running low. The Colorado Trail has tons of water, but there are still stretches of maybe 20 miles where you do not find any drinkable water without leaving the trail. The Databook tells you to water up at one point in Segment 26 because it is the last reliable water source for 22 miles. I filled all four of my liter containers at that point, which added about 8 lbs. to my load (about a gallon). You do what you need to do. And you will learn and fully understand how absolutely critical water is. Fortunately, all the way along with the CT, under normal snow/rain conditions, fresh, clean water is plentiful. Also, find a filter that you like and test it out. I used a Sawyer Mini water filter and used their spare plastic bags for dirty water. There are lots of choices, but water filtering is critical and you need to find a filter system that works for you.

I was happy with my equipment choices. I ordered a super lightweight ULA backpack that was designed for my 6’3” frame. It still wore on my bony shoulders but had lots of functional storage and very comfortable hip straps that bore most of the weight. I was really happy with its storage space, weight, and durability.

I paid about $200 for a Kelty 20-degree sleeping bag that was as much as a pound lighter than most brands with the same temperature promise. One night, camping a little higher than 12,000 ft near Silverton, it got down to about 20 degrees, yeah, in mid-July. The bag kept me warm, but I also kept on my clothes, gloves, and puff jacket that night.

I also opted for a Big Agnes Fly Creek 2-Person tent, rather than a 1-Person tent because my daughter was going to share it with me the first week and the weight wasn’t that much more than some of the one-person tents. When I used the tent alone, I could bring my pack inside easily. I bought inexpensive food bags from Walmart and hung food in trees with parachute cord each night, except when I camped above the tree line, which was only about 3 nights. I kept my hiking boots and all my gear inside the tent at night after hearing one hiker say that he left his stinky shoes outside and mice or some kind of rodents ate the tongue off one boot.

Shoes/boots are so critical. Protect them. And even when they are your friend, they will probably fail. My Solomans wore through at the heel on my left shoe at around the 350-mile mark (plus training miles in Florida that probably wore another 70-80 miles off the life of the shoes). I did not notice the blister until I felt a twinge and removed my shoe and sock. When I pulled the sock off, the skin over the blister peeled off with the sock. I had moleskin and some gauze padding to repair the shoe/heel area and also cover my blister, but the next three days were pretty tough doing 16+ miles a day. It pretty much hurt every step and got to be a bit of a mind game.

By Day 4, the blister had pretty much calloused over. I cleaned and re-bandaged it two or three times a day, but had to be conservation with my supplies.

I also had a thigh injury. I strained my upper thigh muscle when I was hiking with my brother, Nat, just south of Twin Lakes. We had done about 15 miles and my upper thigh started to really hurt. Pretty much every step. Sharp shooting pain through the large muscle at my right thigh. I knew I had been pressing to keep up with my brother, who is pretty much a Bigfoot hiker, long strides, relentless pace. He is only a year and a half younger than me, and I was over 150 miles into the hike when he joined me, but he was a stronger hiker. I had a hard time accepting that. So did my thigh muscle.

I freaked out a little bit when we finally made camp. If my thigh hurt this much the next day, there was no way I’d finish. No way. I couldn’t help but think of all the people that would be disappointed in me, that I had committed to do this, raised money to see me finish, and no one would be more utterly disappointed if I failed to finish than me. I would have been crushed.

We camped near a small stream that was perfect for freshwater and after resting in my tent, I walked down to the stream and soaked my leg in the freezing water. I found a little pool of about 16” deep and held one of my Crocs on the river floor below my knee so I wouldn’t have to kneel on rocks and did a full 5-minute soak, right up to my crotch on that leg. I literally counted the 300 seconds. I think the water was about 40 degrees. Nat took care of gathering wood, making a fire, cooking dinner, and asking if there was anything he could do. I lay in my tent, anxious, but thankful he was there. In the morning, I felt so much better and hiked with no pain until about the 12-mile mark in the afternoon, and the pain returned stronger than before. I soaked again. Nat took care of everything again, even offered to carry my pack, but I was hurting and wondered if this was the call-it-off point. I was fucking devastated to the point of tears.

The next day I soaked at every creek we crossed. Nat was patient. I hurt at the end of the day but had managed another 16 miles. By Day 4 from the start of the thigh pain, I was healed. The pain was gone. It was a little bit of a miracle, but the pain was gone. The icy river water had saved me, plus some Ibuprofen, and a good hiking partner. I maintained “my” pace, and didn’t let my brother’s hiking pace draw me into a competitive race. I was utterly joyous to be pain-free. Lesson learned.

The last 19 days of the hike, I hiked alone. The first 55 miles I enjoyed the company of my daughter, Mackenzie. Then I met my friends John “Howie” Howard and John Million in Breckenridge and they hiked with me down to Twin Lakes, where my brother Nat swapped the rental over to them, we re-supplied, said our farewells. I asked my buddy, Howie if he was glad he came and hiked his 75-80 miles. “That was the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” he said, “And yeah, I loved it!”.

My brother hiked 150 miles with me. I remember Nat asking me, when my daughter came to pick him up in Saguache where we had hitched a ride to meet her, “What is your biggest concern heading out alone?” And my answer was, “I don’t really have any. I got this”. I actually was OK with being alone. I had great support in the first half of the hike, and alone time did not frighten me. I did meet other hikers and spent some time hiking with them, but tried to maintain my own pace and did not worry if or when we split up. Nobody really hikes “your” pace, but you. I found the alone time to be extraordinary. One day, only one, I didn’t see or cross paths with anyone. Not one person. How often can you say that?? I thought it was phenomenal.

I met a hiker whose trail name was Happy Hour, a microbiologist from Boulder who had hiked the CT in 2010 and just wanted to do it again in 2015. He was probably a few years younger than me, but wouldn’t shake my hand when I offered, so I thought maybe he was just a dick. He told me about an outbreak of a Giardia on the Appalachian Trail one season that was basically from door handles at the various outhouses along the Trail. It sickened dozens of hikers to the point of hospitalization and damn sure ruined their Thru-Hikes. He was before his time with the whole “anti-handshake” thing and I did understand. You simply cannot afford to get sick and expect to meet the physical demands of the hike. My white blood cell count had been down since I first started doing my chemo treatments, and I felt like my resistance was at a minimum. Happy Hour taught me a good lesson. Stay healthy first. Be friendly second.

Happy Hour also told me, “ You don’t want to get caught on Snow Mesa during a storm, that is the last place you want to be.” And he was right.

My first serious lightning scare was in segment 20 in the La Garita Wilderness. Not many people down there. Long stretches without seeing anyone and a long way from any town or resupply. I was hiking over a ridge at the base of San Luis Mountain whose peak just breaks the 14,000 ft. threshold. It was only 11:00 am, and I could see three tiny specks on the summit trail and knew they were hikers heading down, so they had planned well and summited before 10:00 or so. But it was getting scary dark fast and it was easy to tell by the thunder that the storm was closing in. The saddle I was going over was at about 12,600’ and fully exposed, but the trail was heading down into a beautiful bowl. Once I got to the peak I began a full run downhill, as fast as I could with a 30-pound pack, to get lower into the bowl. Lightning started cracking. One flash, then quickly another. Then another. I’d count the seconds between the flash and the boom and it was getting scary. Flash…three seconds, boom. Flash…two seconds, boom. Flash.. one second, BOOM. I ran as fast as I could down the trail. And then there was no time between flash and boom. I opted to dodge off-trail further into the valley, as low as I could get, as fast as I could go. I picked a spot by a small stand of trees that were smaller than most, next to some boulders that were smaller than most. And it started to hail. Just small pea-sized hail, but relentless and cold. I tucked under the trees and looked up to see the three hikers that had summited San Luis. They had made it to the saddle where I had been 20-minutes earlier and were on a full sprint down the trail. I did a prayer for them and also prayed that I would not have to hike back up that section to do any CPR on these people if they needed it.

Lightning is so freaking scary, so plan your peak days well. And within 30 minutes, the sky was clear and blue and the frightening storm was completely gone. Grass and flowers were already drying as it had never happened, but I was still shook. That is Colorado.

I planned well for Snow Mesa, with Happy Hour’s words etched in my brain and still found myself up there completely surrounded by lightning storms. Snow Mesa is a bizarre place. You will hike for weeks and everything is a hike up to a saddle, then down through a valley, and back up over a ridge and down toward the river or creek, but Snow Mesa is a giant mesa at 12,000 ft elevation and has no trees. It feels like the entire peak of what would have been a 16,000’ mountain has been lopped off, like with a sideswipe of an enormous machete, chopped clean and nearly dead level. It is a crazy flat-topped mesa after you spend days just hiking up and down through beautiful jagged peaks. And the mesa has at least four “false peaks”, so every time I thought I was up and over the last mesa, I looked out over another mile-long expanse of no protection. Had it been a beautiful day, I would have just soaked in the beauty of the place, lounged, had lunch, maybe even napped. But the lightning storms were nearly completely encircling me and strangely all felt like they were getting closer. I ran across nearly the 3 mile stretch of the Snow Mesa fearing that I was 100% the tallest thing on the mesa. I had an incredible view of lightning storms in three of four directions and saw my best option to avoid a heavy lightning strike if it came down to it, was to lay in a dry gully and pray. But I kept moving.

I met two hikers on the CT traveling with a dog named Tenielle. Turns out one of the guys was blind and went by the trail name Zero-Zero (I finally realized the name was in reference to 20-20 vision, and he was 0-0). His dog and his buddy, Just Dave, were his guides. He had hiked the Appalachian Trail, the Pacific Crest Trail, and was actually sponsored by a hiking shoe company to do Thru-Hikes. Their pace turned out to be just about the same as mine and we would leapfrog each other nearly every day. I met the guys in Lake City, a 20-mile hitchhike from the Trail when the forecast called for 100% rain and lightning for two days.

“It’s good to be tenacious, but you also have to be smart and not die out here, “ Zero-Zero had told me, so I followed them into Lake City and met up for dinner. I told them about how much Snow Mesa had scared the shit out of me and they both laughed but also nodded that they had their scares with lightning.

“The thing about this Thru-Hiking, and Zero and I have done plenty,” said Just Dave, “is that you can go several days, four or five, that is a bit of a grind, that nothing all that memorable happens and then something scares the shit out of you, and by God, you don’t forget those times,” and he sipped his beer.

“And when you try to tell somebody what it is like, the hike, the day after day, they just won’t understand wet socks,” and he tipped his beer to me and I knew exactly what he meant. Some days you start out with wet socks, and if they aren’t wet when you start, they sometimes get soaked ten minutes into your 8-10-14 hour hike day. You learn to accept and deal with a lot of stuff on the Trail. The lack of a shower. Tight sleeping quarters. A 2” thick blow-up mattress that barely keeps you off the ground when you roll on your side. Rain. Mosquitoes. Having to filter every bit of water you drink. The same old food, or not enough M and M’s. Sore feet. Sore shoulders. And wet socks. “They will never understand wet socks,” Just Dave had said.

And while you endure, you find out how fucking glorious a hot shower is when finally get to take one. Or how incredibly nice it is to have someone bring a fully cooked meal and a tall glass of ice water if you just order it and pay for it. And how beautiful a bed and mattress really are. You also bow to the elements and realize how small you are, how grand Nature is, and yet still feel that your presence is vital to the world, even if only to a small group of family and friends. And you have time to think…and dream…and give thanks…and sing where nobody is around to hear how off-key you may be.

The moments that scare you etch in your brain. So do the views that you just want to soak in. That is one thing about the Colorado Trail that Just Dave commented on when he said, “The views on this Trail are incredible. On the AT, you are encompassed in the forest and rarely get the long views that are just about everywhere on the CT,” and I wondered how hard that was for Zero-Zero to hear. Zero’s journey and experience were really much different and hard for me to imagine.

One moment for me didn’t really frighten me but will be with me forever. I have camped alone in a perfect little high mountain meadow and was up at first light with a small fire going, a cup of hot coffee in my hands when I heard a crash down through the bushes and brush close by that sounded to me like a mountain biker that must have gone off the trail above me and crashed down through the mountainside, snapping limbs on the fall. I waited to hear a cry or scream and heard nothing until an incredibly beautiful buck elk with a 4-5’ wide rack and at least ten points came trotting across the meadow. He was clearly too embarrassed to even look at me knowing that he had just stumbled and fallen down the side of the mountain. Of course, then I wondered if maybe a mountain lion had tried to take him and forced him to take such a fall. I didn’t see grown elk as being clumsy and I was on my guard all morning that day.

The southern end of the CT is utterly spectacular. That is one reason I would never recommend starting in Durango and ending near Denver. I got to spend the last 12 days alone and texted my wife that I was going to try to “cherish each day”. Her response was that it was time for me “to come home and cherish her”. And I get that and thought so many times how critically important it was that she supported me to do the CT, to be gone that long, to know I needed it. She would meet me in Durango and I’d get to tell her all about “wet socks’ and already know that she wouldn’t really understand.

In Segment 24, I missed a turn. It was marked, but I literally walked by the wrong side of the marker, had my eyes focused on a post, and a small cairn (rock pyramid) that had marked much of the trail when the small metal CT signs were not tacked to trees. I was hiking at 12,000’ and there were no trees. I had spent the previous night with my food stuffed in my tent, covered with stinky socks as a defense because there were no trees to hang my food bag as I had every previous night. I did not like having my food in my tent.

So I missed the turn and kept following the well-worn trail following cairn after cairn with the feeling that I was off track. There hadn’t been a CT marker in several miles, but my general JPS (Josh Positioning System) kept feeling that my direction was right on. My brother Nat carried with him an actual GPS tracker specific to the Colorado Trail and if we had any doubt if we had missed a turn, he’d just check and we would correct our mistake. I suggest you have a tracker as he did. I could have died that day.

I continued the wrong way for about two hours, about 4 miles. I got to a beautiful mountain lake that was a rich aqua color like I’d never seen. I guessed it was deep and when I worked my way down to the shore I realized it dropped off into serious depths.

The entire shore was a rock pile. The adjacent mountainside had literally fallen into the lake and there were millions of granite rocks and boulders covering the side of the lake where the “trail’ had led me. I could see a gap and another cairn at the far end of the lake and started that direction stepping from boulder to boulder. I had in mind an “I Shouldn’t Be Alive” episode where a guy gets off-trail, traverses a similar rock field, and has a rock roll on his leg, pinning him 30’ from the water. His dog survives, but rescuers find him a week later dead from dehydration.

At the end of the lake the trail is just not there and I know I screwed up and I am super pissed at being so stupid. Instead of re-risking the traverse across the lake boulders I decide to short-cut and high road across the steep loose talus on the mountainside. Incredibly sketchy. I thank God for my trekking poles that my friend Howie had loaned me at about the halfway point in the trek. I had never really liked using trekking poles on my day hikes and hiked the first 250 miles without trekking poles. The poles may have saved me from tumbling down the talus slope and into the lake. I will never again hike without them.

I had a Spot GPS beacon with me. I pressed the right buttons each night to let my wife know I was OK and so she could track my progress, and had a button sequence I could use if anything dire happened and I needed to call in rescue services. I seriously thought, if I go into the lake, I will need to ditch my pack to keep from drowning. And there will go all my gear and my Spot. And it was 20-degrees the night before. So I was scared. Breathing to make sure I kept it under control. And took it one step at a time. When I got to a safe area and knew all I had to do was backtrack to where I had missed the turn, I was incredibly relieved and also angry at myself for being so stupid that I didn’t eat or drink until I got back to the turn. Then I stopped and rested. It had been a four and a half hour mistake and had scared the shit out of me. I am not sure if I had gone into that lake if anyone would have ever figured out my mistake or found my body. Lesson? Shit can happen. Be as prepared as you can be. And try not to be stupid like me.

When I was 75 miles from Durango, I felt like it was all downhill. No way I wouldn’t finish. I met a female hiker in the area after Molas Pass near Silverton. It was rainy but cool and we hiked a while together and I asked what she was doing out there by herself, “Just healing,” she said. And I didn’t ask anything further. I think for lots of people, there could be no better therapy than getting into the mountains, allowing yourself time to heal from whatever ails you.

Her name was Sarah, from Durango, and said her daughter was 19 and had taken a semester off from the University of Colorado and traveled for 6 months. She had volunteered in a hospital in India dealing with desperately poor people, and traveled extensively through Africa and was having a really tough time with “re-entry”.

“What do you mean, re-entry?” I asked.

“My daughter is a different person now. Having traveled, having seen parts of the disadvantaged world, and all the petty chatter and partying with freshmen and sophomore kids at UC is, well it’s not like beneath her, but she tells me she just can’t go there…it’s just too trivial and hard for her,” Sarah told me. So I was introduced to the term “Re-entry” and gave it lots of thought. When Sarah turned to do her 3-day loop and I continued south, she said, “Good luck with your re-entry,” and smiled.

Thru-hiking will change you. I told my mom when I got back that the hike had changed me forever, but, of course, she didn’t understand “wet socks” or really what I was talking about and I couldn’t fully explain. My daughter Mackenzie had a 50-mile “glimpse”, and I know she got it. Howie, John, and Nat all got a sizable glimpse, enough to know if doing more is in the cards or not. Other people don’t have to understand. It is your trip. Your adventure. Your experience. I hope you persevere and make it the full distance. Do something big. That is what the female hiker told me, yeah the one I had seen on Day One, the one I would have never bet would make the distance. I saw her on my last day, just outside of Durango. “I know you!” we both said.

“I gotta tell you,” I said, “I never thought you would make it to the end when I saw back at the beginning. What made you finish?” I asked.

“I wanted to do something big…something big… yeah, I guess that’s it. And fucking A, I am 5 miles from the finish,” she said and teared up. I gave her a high five and we both managed our own pace to the end.

So go out there and do something big. And be safe. I finished in 38 days, with four Zero/no mileage days. I started the hike at 209 pounds, about 8 pounds over what I consider my “fighting weight”, and finished at 178 pounds. Over 30 pounds lost. I felt as strong as I have felt in 25 years since training for a marathon but didn’t look healthy, saggy butt cheeks with no fat at all. But please don’t worry about me, I gained it back and enjoyed all the pizza, IPAs, and ice cream everyone tried to feed me.

I read in the Durango paper that Zero-Zero, Just Dave, and the dog Tenielle had finished two days behind me. It made me smile to read the article.

Also, I had left my journal in these nice sisters’ car, ones who had given me a ride from Saguache back to the Trail after dropping my brother off. I had written in it every night on the trail and was pretty devastated when I realized I had left it on their back seat. I told Mackenzie about what had happened and she was like, “We’ll get it back. What were their names??”

I could only remember one sister’s name and that they lived in a small town south of Saguache. Mackenzie got out a map, and I guessed it might be Monte Vista and she called the Monte Vista Chamber of Commerce to see if they had a Sonya in their town.

“Why yes, she works at the hardware store right next door, you want me to walk over and see if she is there?” Incredibly, it was the same Sonya who had given me a ride and I found that she had sent my journal to the Colorado Trail Foundation in Golden, Colorado. I’d later connect with Bill Manning at the CTF who said, “Are you kidding me, you are the Josh?!” Nowhere in the journal had I left my last name or address. But Bill sent it to me in Florida after we talked and I was ecstatic to get my journal back, and frankly could not have written this without it. It also made me feel better about the world, about my faith in the good of people, and about all these connections that seem unrelated but are a huge part of the experience.

I wrote to Sonya and to Bill Manning and thanked them both. And though I am not a church-goer, or affiliated with any religious group, being in the wilderness made me feel closer to God, closer to the people in my life, and closer to those that have passed on. It is plainly and simply, a powerful experience.

So do it. Find your pace and own it. I met a guy in Gainesville two years after doing the CT and found out that he had completed the Appalachian Trail in 58 days, unassisted, meaning he had no road crew to bring him food or help in any way. He averaged 48 miles a day, for 58 days. 48 miles a day, for 58 days! He was one of those elite distance guys, just an incredible beast and a super-nice guy. Crazy endurance strength and I was in awe. But he also told me he had done the Colorado Trail and it took him 50 days. Let me re-state, he had enjoyed the Colorado Trail for 50 days. So please, never, ever forget to enjoy your hike.

Climb the mountains and get their good tidings.

John Muir

Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees.

John Muir

The winds will blow their own freshness into you, and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves.”

John Muir

Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home: that wilderness is a necessity: and that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of Life.

John Muir

My many thanks to the Colorado Trail Foundation and the countless volunteers who help maintain this beautiful Trail and make it possible for people like me to enjoy.

Be safe out there.

Josh Hellstrom, Colorado Trail Thru-Hiker, 2015

If you’re planning to hike the Colorado Trail, leave me a comment below. Good Luck!

If you liked this post, check out my wife’s neat bracelets at Les is More, Designs by Leslie.